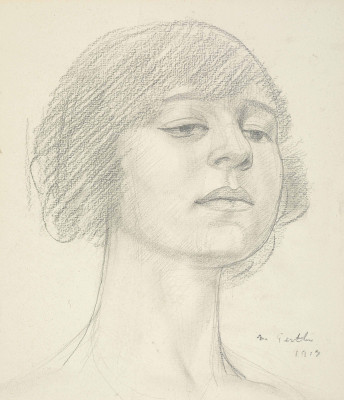

Dora Carrington - Self Portrait, 1913

The British art world in the days before World War One was a curious place, often very staid but also filled with searing modernity and great talent. Now over a century away from us, first-hand recollection has gone, replaced by memoir, hearsay, tales passed down. Yet with current interest high in the more avant-garde elements of that time, it is still possible to detect a flavour of those heady days.

Much of the establishment art world in the early twentieth century was incredibly stuffy. Contemporary art then was a seemingly rather frightening creature, lampooned by the press, unseen in the wider world and very much a London-centric movement. However, the circles that thrived on new ideas were filled with talented artists and memorable characters.

Some, such as Augustus John or William Nicholson, went on to become themselves rather establishment figures. Others, such as Stanley Spencer, David Bomberg or Wyndham Lewis, created incredible bodies of work that still resonate today. But some have simply slipped away from our notice.

One such figure is Dora Carrington. Hailing from a respectable Victorian family and possessing a formidable aptitude for drawing, she came to study at the Slade School of Art in 1910 and thus was part of a golden generation of talents that included Spencer, Bomberg, William Roberts, Mark Gertler, Christopher Nevinson, Paul Nash and others. Fighting the prejudices of the time in a very male-orientated world, she and her circle of friends make a remarkable group of women and Carrington, as she preferred to be known, was at their head.

Slade Picnic, 1912, including Stanley Spencer, David Bomberg, Gertler, Carrington, William Roberts and others

Yet her star has dimmed rather over the years. She did not particularly seek to exhibit her work and thus for many years her art was rarely seen outside the circle of friends in which she mixed. During the 1920s her output, never large, shifted away from painting to decorative schemes and her early death by suicide in 1932 at the age of 39 saw her reputation gently fade away. Exhibitions and biographies in the 1970s began to reawaken interest in her work and life and a large retrospective in the 1990s and a major film about her life, starring Emma Thompson and Jonathan Pryce, shone a new light on this rather shy, self-effacing but incredibly talented artist.

We however will rewind ourselves back to 1913. At this point, Carrington was almost at the end of her time at the Slade. She was considered one of the most talented students of her generation and was also a memorable figure as a person. She won prizes for her work and was involved in a relationship with Mark Gertler, another prodigious talent. As an individual she had challenged the norms of the time by discarding her Christian name, cutting her hair short and wearing clothes that in post-Edwardian London would certainly have raised eyebrows.

Mark Gertler - Head of Carrington, 1913

In her 1913 Self Portrait, Carrington makes a very bold statement, both as an artist but also as a person.

It is useful to remember that in 1913 when Carrington was creating this work, the women’s suffrage movement was still very active and photographs from the time show even these most radical women still largely dressed in styles that conform to those of the day with long skirts and high-necked blouses. Yet Carrington chooses to present herself in a striped man’s shirt, a peaked cap and a pair of hugely baggy workmen’s trousers. Her hair is cut short in a bob and her stance, a turning contrapposto leaning against a door frame, is not at all what a female portrait of the time would have been expected to show. The whole impression is a remarkably potent self-image.

Although some early exhibition entries for this work mention in the title “Slade Student in Fancy Dress” and indeed her brother recalled that when Carrington cut her hair short she had told her conservative family that it was for a fancy dress costume, this is more likely a gloss over the main issue. Carrington is presenting herself in a very particular way which even now looks remarkably bold. The pose and dress are both designed to show off the artist’s self-image and her great skill in rendering it. From the shine of the patent peak on the cap to the folds of the heavy indigo trousers contrasting with the lighter material of the shirt, this is a tour de force of observation. The pose is remarkably complex with the twist of the figure and the way she distributes her weight all demanding a complete understanding of the human figure and great confidence in one’s ability to render it convincingly.

There is a confidence and boldness in this image which feels perhaps at odds with the Carrington who peers out at us in the photographs of the time. Images exist of Carrington at around this period, often with her painter friends such as Dorothy Brett or Gertler, or later with Bloomsbury friends like Lytton Strachey and we see her seeming rather shy, peering out from under her fringe, determined to not be the centre of attention.

Carrington with Dorothy Brett and Barbara Hiles, c.1911

This contrast between her painted self-image and her appearance in photographs would be striking enough were it a usual method of presentation for the artist. Yet this painting is a remarkably rare self-portrait by Carrington. An early drawing of around 1910 exists, now in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, and a rather stylised woodcut in the form of a faux postage stamp from around 1916 but little else is known. Therefore, the re-emergence of this striking and accomplished work is not only a great boon for students of her work but also a significant addition to our knowledge of the activities of women artists in the avant-garde in Britain prior to WWI.

However, there is more. When we were researching the history of the painting, we knew that it had been bought from an exhibition in 1968 put on by the young Anthony d’Offay. He was one of the instrumental figures in the 1960s and 1970s revival of interest in British modernist art from the years around the First World War and thus his handling of this painting made perfect sense. But where had it been between its execution and 1968? Carrington rarely exhibited after she left the Slade and there had been little interest in her work after her death. This suggested that it may have been in a collection that was close to the artist but we had no proof that had been the case.

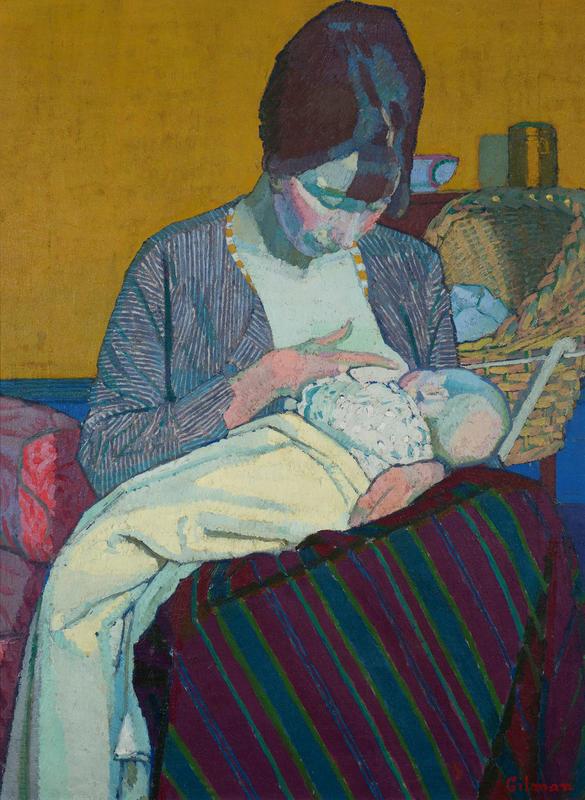

In 2018-19 I co-curated an exhibition of the work of Harold Gilman which brought me into contact with the artist’s descendants. Gilman himself had died in 1919 at the age of only 43, a victim of the Spanish Flu epidemic that caught so many. He had recently remarried and had a young son who was little more than a babe in arms when Gilman died. His wife, Sylvia, was the model for a number of Gilman’s later paintings, including the important Mother and Child now in the Collection of Auckland Art Gallery, New Zealand.

Harold Gilman, Mother and Child, 1918

Sylvia was also an artist, having been a student at the Slade in the pre-WWI years and indeed she can be seen in the famous 1912 picnic photograph seen above, seated behind Carrington and Brett, her hairstyle familiar to us from the later Gilman paintings. Whilst hardly known now, Sylvia’s work clearly was of high quality, as her Portrait of a Girl in the UCL Art Museum shows, but it appears that once she was married and then widowed, her artistic output diminished drastically.

Sylvia Gilman (nee Meyer), Portrait of a Girl

Whilst at the Slade however, Sylvia had become good friends with Carrington and Self Portrait was acquired directly from the artist, almost certainly as a gift. It remained with Sylvia until sold in 1968, an event that her granddaughter remembered clearly having herself become very attached to this stylish and charismatic image that hung in her grandmother’s house.

We are pleased to announce that this important work, a gift from the artist to a fellow painter, only ever on the market once before in its history and unexhibited for over twenty years, has been acquired through J & J Rawlin Ltd by the Jerwood Collection and thus will once again be able to be seen by the public and add to our knowledge and understanding of this neglected artist and the period in which it was made.