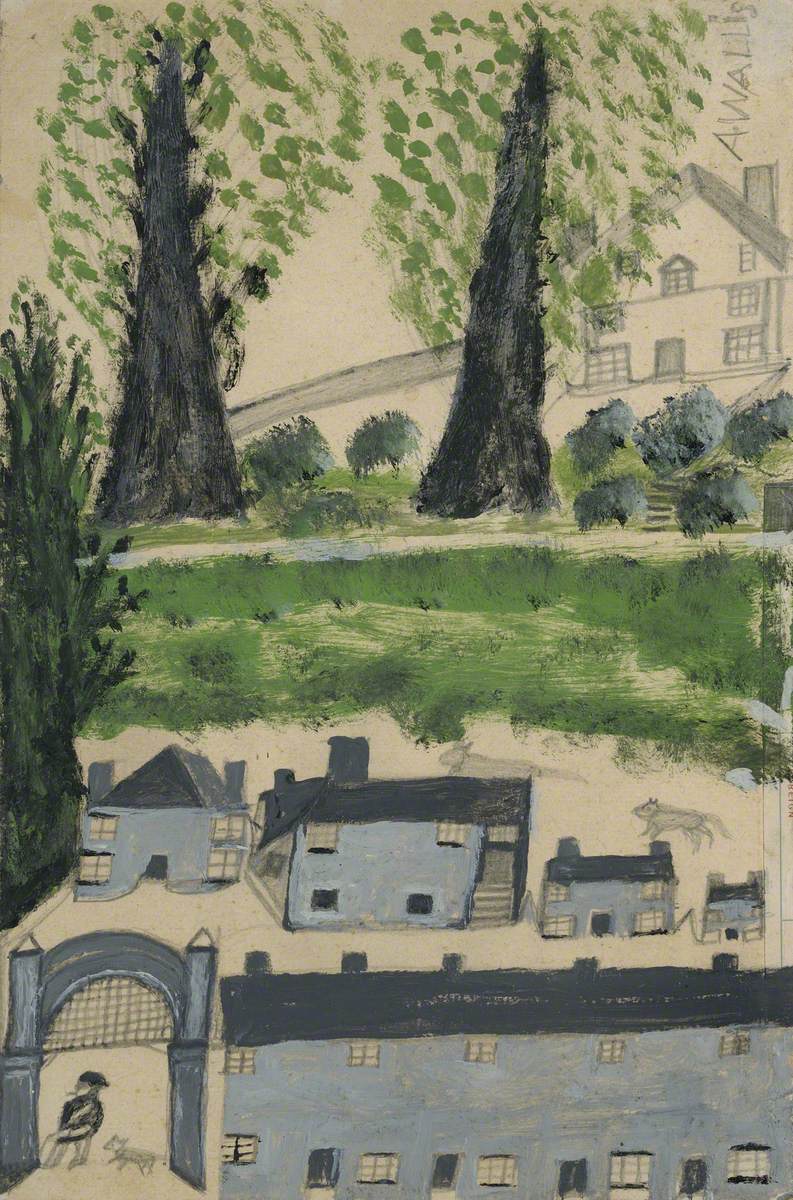

White House and Cottages, the Old House, Porthmeor Square, St.Ives (Kettle's Yard Collection)

Almost a century has passed since a somewhat mythical meeting in modern British art history occurred. In the August of 1928, two artists, Ben Nicholson and Christopher Wood, were staying with friends near Falmouth in Cornwall and took a day trip over to St.Ives. Whilst there, they encountered Alfred Wallis, a diminutive and widowed retired mariner who had taken to painting in his old age and was living in a tiny cottage in the town.

Ben Nicholson and Alfred Wallis outside Wallis' home, No.3 Back Road West, St.Ives

The story of the two artists seeing the paintings of boats nailed to the wall by the door of the house is well known and as recalled by Ben in later years it makes for a very dramatic Damascene conversion. Wallis’ work was in fact already known to one or two other artists prior to the Nicholson/Wood ‘discovery’ but it was Ben and Kit’s recognition that these paintings, roughly produced on any pieces of board or card that came to hand, offered a unique vision which combined the experience of a lifetime with the untutored spontaneity of a child and they helped bring his work to an appreciative audience. For forward-thinking artists of the period, the engagement with the most direct expressions of thought and feeling in painting needed to be as pure as possible but of course after years of academic training, most artists found it hard to throw off their learnt ways of seeing and doing. Wallis therefore had exactly those qualities of being able to translate experience without learning which British art was searching for at the time and he was therefore a prime candidate to become its own ‘primitive’ master.

Whilst it is now almost impossible to think of the history of modernist British art and especially that of St.Ives in the twentieth century without reference to Wallis, it should be remembered that for at least two decades after his death, his work was very much the closed preserve of a small and interconnected circle of artists, collectors and critics.

Although Wood was very open in his letters about the influence of Wallis on his work, his early death in 1930 meant that the mantle of spreading the word fell on to Ben Nicholson and he approached the task with gusto. Within a few years, those in Ben’s circle all knew about Wallis and were collecting his work. Some, such as the critics Herbert Read and Adrian Stokes visited Wallis and experienced the old man’s sometimes irascible manner at first hand. Barbara Hepworth remembered being lectured on ‘decent behaviour’ by Wallis and Lanyon was only allowed to buy a painting from him if he promised to read the bible every day. Others, such as H.S.’Jim’ Ede corresponded over a long period with Wallis and received regular parcels of paintings tied up with string in the post – they selected the works they wanted and sent the rest back with a cheque. The prices paid were, to modern eyes at least, miniscule but it seems that the old man was happy to be recognised by those he considered ‘proper’ artists.

As time passed, the message spread. Herbert Read included a work by Wallis in the first edition of his influential 1933 book, Art Now, and others were reproduced in the periodical Cahiers d’Art. Nicholson presented a painting to MoMA in New York and collectors as varied as as Lucy Wertheim, Leonard and Dorothy Elmhirst, Helen Sutherland and Eardley Knollys began to build up quite sizeable groups of his works. The works were often gifted, and indeed sometimes the gift of a Wallis could indicate your acceptance as part of the circle. Terry Frost, a leading figure in St.Ives in the 1950s but of a younger generation than Nicholson, told the author in conversation that ‘…being given a Wallis by Ben meant you really knew you’d arrived!’. A glance at the lists of owners of the works reproduced in either of the two early monographs on Wallis, published in 1949 by Sven Berlin and 1967 by Edwin Mullins, offers up only a handful of names, but virtually all of them were broadly involved in what one might call the ‘modernist’ wing of British art. In the 1960s and 1970s some London galleries began holding selling exhibitions of Wallis’ paintings, such as Piccadilly Gallery, Waddington Galleries, Mercury Gallery and Crane Kalman, from which the awareness and ownership of his work began to spread.

Now firmly established as a key figure in the art historical canon of modernism in Britain between the wars, we have also seen the focus on his work become gradually more and more fixed on the maritime subject matter. Whilst the sea and the coast are clearly absolutely central to Wallis’ vision, and the idea of the elderly mariner recalling the voyages of his youth is one that has clearly touched the imagination of many, we do run the risk of side-lining or indeed just ignoring a large part of his work which is every bit as closely related to Wallis’ own remembered past and which appears to have been very important to those who were the pioneers in collecting his art.

Ben Nicholson felt that Wallis was adamant that his paintings were the old man’s memories of actual events or places he had seen and the recent study of his life seems to back that up. Ship’s documents from the early years of Wallis’ life have established that he did indeed go on long transatlantic voyages in the age of sail and danger and we can therefore take it that these memories are what he sought to express in his work. The paintings, which at first sight seem so simplistic, have an internal logic which expresses the essential qualities of the subject without feeling any need to conform to the usual visual guidelines we develop and come to expect. Scale, distance and proportion are never apparently important to Wallis, but he uses them in the service of the narrative of his work to emphasise or diminish the elements he chooses.

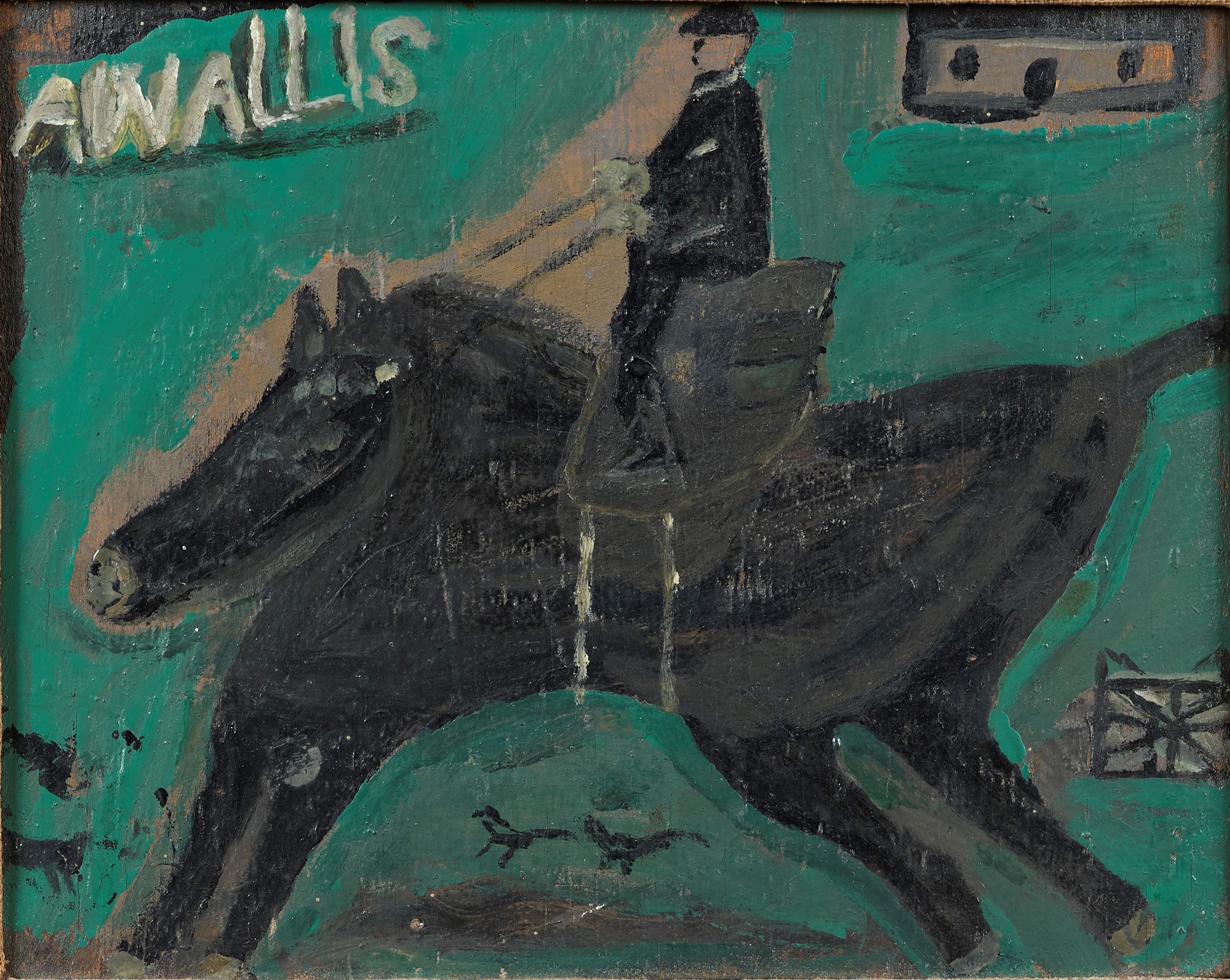

Alfred Wallis, Houses with Rider (formerly Scott Collection)

This apparently unconscious way of tackling his subjects could well be the key as to why so many artists have found themselves influenced or impressed by Wallis yet without the need to try and copy his style. From Ben Nicholson and Christopher Wood through Barbara Hepworth, Denis Mitchell, Terry Frost, William Scott, Patrick Heron, John Wells, Margaret Mellis, Wilhelmina Barns-Graham, Peter Lanyon and others, the list of artist owners of Wallis paintings is a fairly comprehensive Who’s Who of the period. Amongst these, as any perusal of the owners lists in early exhibition catalogues or books on Wallis demonstrates, quite a substantial number of pieces owned by artists were not just the pure marine images. Wallis’ ability to solve painter’s problems of space and subject, regardless of whether he knew he was doing it or not, does appear to have been an important factor in the acquisition of Wallis works by artists and indeed Edwin Mullins looks at this very topic in his book. Recalling a conversation with William Scott about Scott’s own Wallis, Houses with Rider, he notes how Scott admired the way in which Wallis instinctively knew how to render the walls and houses in a convincing way, something that Scott himself had been working on for many years. Indeed, if one thinks of Scott’s paintings of cottages in Brittany produced in the late 1930s, it seems quite correct that this particular Wallis should have become his.

Acquired by William Scott from Jim Ede in exchange for one of his own works, Bowl (White on Grey) now in the Kettle’s Yard collection, the correspondence between him and Ede suggests that Scott recognised the artistic value of Wallis’ work and was worried that the swap was not a fair one.

William Scott, Breton Landscape, 1938-39 (Private Collection), image courtesy of the Estate of William Scott

Whilst the maritime paintings by Wallis are often considered as memories of a particular journey or event on a journey, something that recent scholarship has been able to attach to particular ships and voyages taken by Wallis as a young man, the landscape or figure paintings feel rather less easily understood. The places are rarely identified and as we know Wallis was not aiming for a topographical depiction, the clues for identification are limited. However, the impression of a Wallis painting which can make a boat rushing over turbulent waves feel completely authentic does extend to works such as these too. The placement of buildings usually suggests that one is seeing them from the water as the coast passes and his ability to insert, perhaps without particularly thinking about it, details that tantalise adds significantly to the drama of these paintings. Houses are usually presented in a row, and there is often a tendency for them to follow the line of the support he is using. The closeness to the picture edge suggests they may be intended to be read as being near the water’s edge and indeed many of the small coastal settlements along the Cornish and Devonian coasts with which Wallis was familiar do run right down to the sea.

Alfred Wallis, Houses and Trees

Houses and Trees is just such a painting. A single house stands cheek by jowl with a larger building, their frontages mirroring the curve of the millboard on which they are painted. A low wall defines the foreground and distance and typical Wallis gates provide the access points between what he very definitely establishes as here and there. The houses appear old, both in their architecture but also in atmosphere and it begins to dawn on the viewer that whilst the larger building is rather more rustic than its neighbour, it is clearly split into three. The windows are unusual for Wallis in that he makes it quite clear that they are made up of small panes rather than the usual cross bars he mostly uses and that the house is in darkness. This is not immediately obvious until one’s gaze shifts next door. The windows are left deliberately unpainted, using the yellowish ochre of the support to give the impression of lights within. By comparison with its neighbour, this house appears ablaze with light.

Although there are no direct clues as to the source of this image for Wallis, Houses and Trees does bear comparison with an intriguing painting formerly in the collection of Ben Nicholson, reproduced by Sven Berlin in 1949 as Essex Cottages but inscribed by Wallis as ‘Old Place in Essex’. Whilst it seems that Wallis did not make the long ocean-going voyages much after his early twenties, he probably worked on the coastal trade routes which passed along the south coast, through the Channel and up the east coast. These houses, one of which appears to be thatched, do not look like the usual Cornish buildings we see in Wallis’ work and they share the multi-paned windows that are so unusual in Houses and Trees.

Alfred Wallis, Houses with Rider (formerly Scott Collection) Alfred Wallis, Gateway, (Kettle's Yard Collection)

Houses with Rider presents similar enigmatic questions to the viewer and in fact gives the impression of almost being two distinct compositions. The upper section shows a house, again presented squarely to the viewer and bordered by a wall. In the grounds nearby stands a smaller black construction, perhaps a shed or animal shelter surrounded by a white wall. The enclosure is simply painted, a white line that follows the four sides with a small space to enter, but it undoubtedly carries the full essence of the subject it depicts. The lower section of the composition is much more alive, with two rows of houses not dissimilar to those Wallis painted when depicting St.Ives and its winding streets near his own home. Here though, figures walk the streets, an old man with a cap and stick and another passing through the distinctive foreground gate with a dog. A horse and rider gallops across the front of the image, bringing a rush of activity and movement to the composition. The gateway with man and dog is very similar, as is the lower part of the composition, to that seen in Gateway in the Kettle’s Yard collection, and the horse and rider motif also appears in a number of paintings, including Horse and Rider formerly in the collection of Sir Herbert Read.

Alfred Wallis, Horse and Rider (Private Collection, formerly in the collection of Sir Herbert and Lady Read)

One senses that once again Wallis is showing us a memory, a fleeting but significant moment that had impressed itself into his mind and which resurfaced years, perhaps decades, later. Wallis’ letters to those such as Ede or Nicholson frequently emphasise that the scenes in his paintings were real, they were the things he knew and had seen, and whilst with the boats he sometimes names and on which we now know he served or knew can be seen as having a factual element, we are left uncertain as to the meaning in these landscape works. Indeed, to call them landscapes seems somehow inadequate. They are certainly not landscape in the generally accepted understanding of the word, more a visual signifier of clues that form part of a larger experience or story, a kind of pictogram from the past.

Both Houses and Trees and Houses with Rider offer a relatively understandable image and we can see that they can easily be seen as the remembered experiences of the old man translated through paint into a story we can at least begin to unravel.

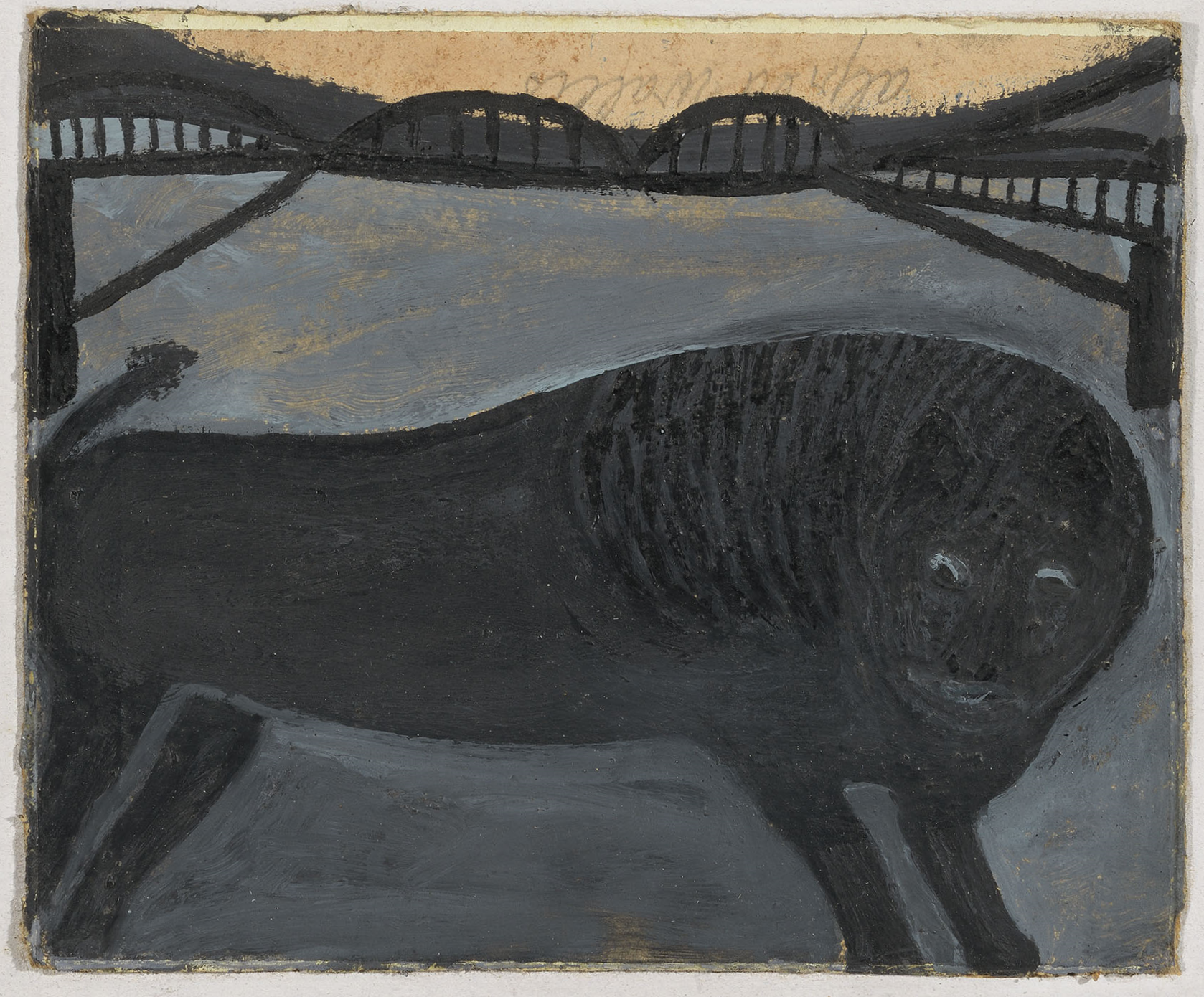

Alfred Wallis, The Lion (formerly in the collection of J.P.Hodin)

The Lion is a much less simple painting.

It is essentially just two images, a black bridge which crosses the entire horizon high up the picture plane and a large lion-like animal. He is also painted in black, but with grey highlights and strong details in the texture and there is something of the heraldic beast about his physiognomy. Like such creations, the connection to the reality of a lion is a little tenuous but there is definitely something feline and powerful about this beast. But who is he and why does he stand before the bridge. Is he guarding it in some way or approaching it? The bridge bears a strong resemblance to the Royal Albert Bridge, the pioneering and audacious double span railway bridge designed and built by Isambard Kingdom Brunel. Spanning the Tamar at Saltash and thus connecting Devon and Cornwall, the bridge was finished in Wallis’ childhood and as he was born and brought up in Devonport, just a short distance away, it seems likely that this celebrated marvel of Victorian engineering must have been familiar to him and perhaps represented the epitome of something rather marvellous. Certainly, a bridge image, usually loosely based on the Royal Albert Bridge, appears over and again in his work, perhaps most memorably in the large painting Saltash which is one of the gems of the Kettle’s Yard collection. In The Lion Wallis renders the bridge with relative accuracy, the distinctive double ellipse shape looming over the grey area that one can read as an expanse of water. But how this connects to the animal of the title is unclear. The heraldic-type stylisation could perhaps suggest the kind of lion one might see on a ship’s figurehead or carved on the stern of an old decommissioned hulk of the man-of-war type we know were anchored around Devonport for naval training. It is also reminiscent of the Coade stone lions found atop so many nineteenth century Black Lion pubs, although to the staunchly Christian and teetotal Wallis such a connection would have surely been anathema.

The simple answer here is we do not know; this enigmatic animal, rather a kindly beast it seems once one looks closely, will surely remain something of a mystery.

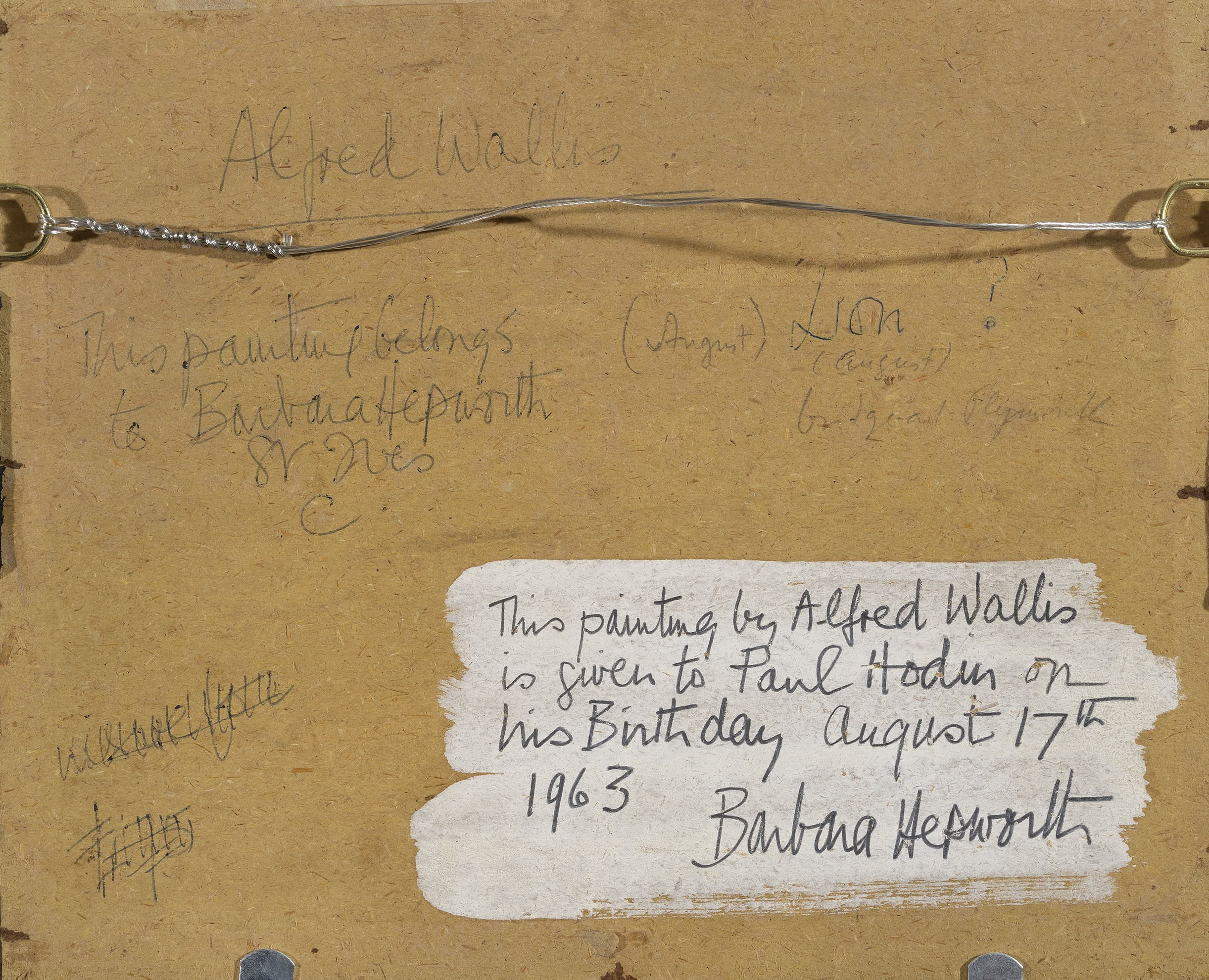

That it was valued and appreciated though is surely without question. For many years The Lion belonged to Barbara Hepworth. Her exposure to Wallis came through her relationship with Ben Nicholson and she clearly shared Ben’s enthusiasm for Wallis’ paintings. By 1932 Hepworth was giving a Wallis painting, presumably from the corpus already gathered together by Ben, to her cousin as a gift but once she, Ben and their children moved to St.Ives in 1939, the opportunity to meet the artist was presented. In a broadcast on BBC radio later in her life, Hepworth recalled the visits with Ben to the tiny cottage on Back Road West and witnessing the clear connection that Ben and Wallis had. She was also given the task of taking Herbert Read to meet Wallis when he was staying with them and heard a marvellous long monologue from the old man to Read about his life. Hepworth owned several works by Wallis, either acquired directly from the artist or gifts to her from Ben and several of these are now in public collections. The Lion was given by Hepworth to her great friend, the critic and writer J.P.Hodin as a gift for his 58th birthday. Hodin had recently published his important monograph and catalogue on Hepworth’s sculpture and it was therefore fitting that such a personal gift was made.

Backboard of Alfred Wallis, The Lion, showing inscriptions by Barbara Hepworth

Much about Wallis’ life remains shrouded in uncertainty but as further facts come to light, it is clear that the art that he made in the final years of his life recalled much that he had experienced decades earlier. His paintings tell us stories from a past that was long gone even when Wallis put them down in paint and the faint voices we hear now continue to exercise the same fascination that they did that summer day in 1928 when Nicholson and Wood walked past his door.