Over the past few weeks I've written some short pieces looking at the recent season of Modern British art auctions across the three main houses, Christie's, Sotheby's and Bonham's. However, if you are a collector in this field, you need to cast your net a bit wider in order not to miss some gems that pop up in those same houses, not in the Modern British sales, but in the Impressionist & Modern and Contemporary auctions.

Over the past few weeks I've written some short pieces looking at the recent season of Modern British art auctions across the three main houses, Christie's, Sotheby's and Bonham's. However, if you are a collector in this field, you need to cast your net a bit wider in order not to miss some gems that pop up in those same houses, not in the Modern British sales, but in the Impressionist & Modern and Contemporary auctions.

Hang on, I hear you cry, how does this work? Well, it works according to a rather odd formula that is partly inherited from the past, and partly the simple exercise of financial muscle. Let's first look at the Impressionist and Modern auctions. These cover a huge timescale and stylistic panorama, reaching from Boudin and Fantin-Latour in the 1860s right up to the very last works produced by Picasso, Chagall, and others in their dotage in the 1970s and early 1980s. As an example of a focus on a period, it's a travesty with no real academic validity, but as a marketing umbrella it works very nicely, pulling together most of the great names of the impressionist and twentieth century world into evening and day sales that offer the buyer new to the market a convenient stopping off point to secure some artistic names your friends and acquaintances will recognise. If you choose well and have the appropriate funds at your disposal, there are still some fantastic works to be had, but mostly these auctions demonstrate that the masterpieces in this field are mostly now safely ensconced in museums or collections they will never leave.

For British artists, the triumvirate of Moore, Hepworth and Nicholson pop up here with regularity, occasionally buttressed by the odd Chadwick or other stray. Why is this, I hear you cry? Well, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, the British Council put their shoulders behind a huge push to take British culture around the world. At a time when the costs and debts of WWII meant that for British industry the mantra was 'export or die', the ability to punt British art as both a financial and cultural export to a predominantly American market that had recently had a wide exposure to European culture was not one to be missed. In this period, American collectors and institutions took British art seriously and collected it with a real passion. However, with the advent of Pop, American collectors started to look to their home shores for the next big thing. When those collectors who had bought British in the 1950s and 1960s began to pass away or reduce their collections in the 1970s and 1980s, the British market for these artists tended to be very particular and, to be frank, quite mean. Thus, when great examples came for sale, it was often not worth shipping them over to London, and as there was no Modern British sale forum in the USA, they went into the nearest approximation, the catch-all Impressionist & Modern auction. We therefore find that from the 1970s onwards, great works by Moore, Hepworth and Nicholson come up in New York almost as frequently as they do in London.

The situation with the Contemporary auctions is similar in that it has developed over a long period, but the position behind it is a little different. Contemporary as a discipline in the auction rooms is really a product of the 1980s, when the realisation grew up that some of the post-war artists did not always sit well with earlier generations. As time passed, it also became clear that such a presentation was likely to allow access to a younger clientele, especially amongst those making new fortunes in the financial and business worlds. In Britain, the Contemporary auctions tended to include an element of emerging art, set alongside the big names, to offer a forward momentum. In the USA, this new art sector was initially less strong, and of course each location tended to have a slant towards its own national art.

However, twenty five years on and of course the current end of the scale has continued to be open, welcoming in each new generation, whilst the start point of roughly the late 1940s has stayed the same. The remit has grown, and now includes a huge swathe of rather aged or indeed dead artists. Not terribly contemporary, but once you have been part of this ever-growing world, you or your estate would not really feel happy to be bounced out into the retirement home of Impressionist & Modern.

There have been the occasional attempt to redress this. In the late 1990s Christie's moved their impressionist works into the nineteenth century, made twentieth century art a whole element from Fauve to Pop, and made Contemporary truly that, drawing a start point at 1970. The art world, all cosy in its established niches, hated it and the experiment lasted two seasons at most. Curiously, in the most recent season in New York, Christie's revived the exact concept of what is effectively Twentieth Century Masterworks, but gave it new clothes as a 'curated' concept auction with a title of 'Looking Forward to the Past', something that itself sounded like an artwork. Packed with big name goodies, it made the highest total of any auction yet.

So where do our British artists fit into this? Well of course in the post-1980 world, we have generated a body of eminent practitioners whose work has been internationally recognised and thus are perfectly suited to a contemporary auction. However, the previous generations have also yielded some important figures, and whilst the majority are no longer with us, some muddy the waters by still being alive. As octogenarians, or in some cases nonagenarians, they provide a valuable link to an earlier world, but surely living a long life should not be the only qualification to be included in the gold rush of 'contemporary'. Let's take as an example Frank Auerbach. Having arrived in England just before WWII, he made London his home and it was the London of the 1950s and 1960s that shaped his art. Yet much of his work, regardless of date, now shares a platform that crosses a very wide artistic spectrum indeed. Try and find a common ground between, say, Warhol, Andreas Gursky, Damien Hirst and Lucio Fontana and you'll be working hard. However, there is one, and it is that they are all artists whose work now is well established in the roster of names that makes up the pantheon of Contemporary.

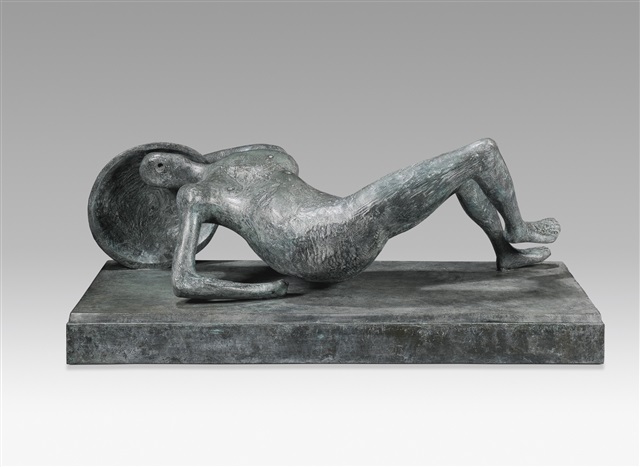

So, in the recent run of auction, what should we have been looking at? As usual, the bigger pieces tended to be included in the evening sessions, and the first on the block was Christie's with their Impressionist & Modern auction on the 23rd June. Perhaps as a reflection of the fact that this department seem to be working closely with their colleagues in Modern British, only one piece by a British artist appeared in this session, a reasonable Henry Moore, Reclining Figure No.2 from 1953, which sold quite well for £1,300,000 (£1,538,500 with premium) against an estimate of £900-1,200,000.

Sotheby's were up the following evening, with a sale generally considered to be of a higher standard than their competitors, and which included six works by British artists. The first to appear, Barbara Hepworth's New Penwith, a white marble carving from 1974, failed to find a buyer at £600-800,000, perhaps something of a surprise considering its appearance coincided with the opening of the large retrospective of her work at Tate Britain, but it wasn't the most lively piece and the estimate seemed fairly hefty. A little later we saw Ben Nicholson's Composition from 1931-36 appear, estimated at £300-400,000. This piece had been bought by the present owner at Sotheby's in 2009 for £325,000 with premium so its appearance here six years later with an estimate of £300-400,000 was a bit of a gamble. As it sold for a hammer price of £350,000 (£425,000 with premium), it just cleared that previous price, but certainly didn't represent much of a return for six years. My feeling on both occasions I've seen this picture is that it is neither one thing nor the other - it lacks the homemade feeling of the early 1930s works, but equally it doesn't have the full, crisp, architectonic feel of the later 1930s.

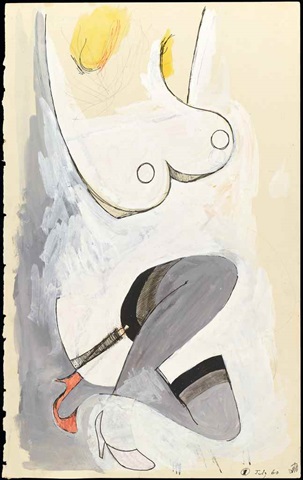

Rather more keenly awaited were the next batch of British pieces. Forming part of a single-owner private collection that was to be sold across both the Impressionist & Modern and Contemporary auctions, this collection was entitled 'Figure and Form' and got the full lavish treatment in the catalogues. Four British works were included here, and the first of them was obviously something people were going to get stuck into. Estimated at £300-400,000, Henry Moore's Two Women and Child of 1948 was a powerful and large drawing, with great colours and the same kind of solidity in the figures that he'd captured in the best of the shelter drawings. When the bidding opened, Henry Wyndham, Sotheby's most debonair auctioneer, was faced with the auction equivalent of a Mexican wave from bidders in the room and on the phones, and by the time it had rushed up to £1,000,000, he paused for a moment to comment 'I think they like this one', getting the expected laugh from the audience. By this point, bidding had settled down to a smaller pool of participants, and steadily it moved on, eventually selling for a hammer price of £1,800,000 (£2,165,000 with premium), a new auction record for a work on paper by Moore.

Similarly the subject of presale chatter, an important sculpture by Moore was also part of this collection. Falling Warrior of 1956-7 is a large-scale work, measuring just over five feet wide and belongs to the period in the 1950s when Moore was absorbing influences from classical sculpture. With seven of the casts of this sculpture from the 10+1 edition being in public collections, this was a rare opportunity to acquire a major work, and with an estimate of £1,800,000-2,500,000, it didn't seem overly ambitiously priced. However, the bidding was sluggish, and the final hammer price of £2,600,000 (£3,061,000 with premium) must surely represent a very astute purchase for the buyer.

Two smaller works followed, Moore's pocket-sized Madonna and Child and Lynn Chadwick's Maquette Jubilee II. Under normal circumstances, neither of these pieces would normally be of sufficient importance to qualify for an evening spot in an Impressionist & Modern sale, but as part of this larger collection they were here, looking perhaps a little out of their depth. Still, both performed reasonably well, the Moore making £200,000 (£245,000 with premium) against an £80-120,000 estimate and the Chadwick bringing £300,000 (£365,000 with premium) against a £200-300,000 estimate.

All quite exhausting you might think, so perhaps we can take a short break at this point before we tackle the Contemporary auctions!