It is not uncommon for an artist to have a strong association with a particular place, but there can be few as indelibly linked with one town as Stanley Spencer. Born in Cookham in Berkshire in 1891, he lived there for much of his life, and even when he was resident elsewhere, this small town was his inspiration, providing the backdrop for virtually all his paintings. However, there is a very important link for Spencer to Suffolk, a link which lasts for almost forty years, and specifically concerns the area around Wangford and Southwold.

Spencer's first experience of the region came via his first wife, Hilda Carline. Herself a talented painter, Hilda had worked in Wangford during the First World War as part of the Women's Land Army, and in 1924 Spencer, Hilda and other Carline family members made an extended visit to Wangford (where Spencer lodged with a Mrs Mills). During the trip both artists produced a number of landscape paintings, including Spencer's Panorama, Wangford Marsh near Southwold, Suffolk (Bradford Art Galleries and Museums).

Already engaged, Spencer and Hilda returned to Wangford the following February, and were married in the parish church of St.Peter and St.Paul on 23rd February 1925. They lodged with a Mrs Lambert at her house, 'The Hill', for a honeymoon and painting trip and were joined a couple of weeks later by Spencer's brother, Gilbert.

So far, so good, and seemingly very straightforward.

One characteristic feature of Spencer's art was the ability for him to be able to produce two very distinctive styles of painting simultaneously. Pure landscape painting, such as in Panorama, Wangford Marsh near Southwold, Suffolk (above), always runs side by side with a more visionary, narrative style, each informing the other. Indeed, Spencer felt that painting landscape helping to keep his work fresh, revitalising it by the need to look so carefully. Spencer's Suffolk paintings of 1924-26 run parallel with his early masterpiece, the huge and complex The Resurrection, Cookham (Tate Britain, London), and whilst at first glance they seem little connected, the artist found the experience of painting landscape an invigorating stimulus to his way of seeing and observing. His vision of the world about him informed the narrative of the great events of his paintings, so when he visualises and then paints the Resurrection, it happens in the places he knows intimately, and the details and ambience he draws into his work lifts the subject from the abstract to the here and now.

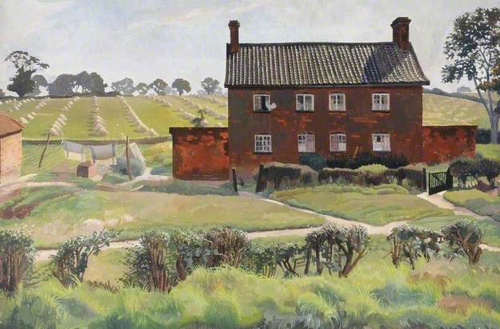

It is this identification of place, memory and emotional response which makes Spencer's connection to Wangford and its environs so important to him. Thus far, it is a place visited with his fiancé, the location for his wedding and honeymoon, and the inspiration for a small body of paintings, such as Stinging Nettles (Private Collection) and The Red House, Wangford (Hull, Ferens Art Gallery), both painted on a further visit in 1926.

However, as the years passed and Spencer's own circumstances changed, the places he had visited in these happier times came to represent something very different.

By the early 1930's Spencer and Hilda had two daughters, Unity and Shirin, he was represented in many important collections, and could be generally considered a major figure in British art. In 1932, the family moved back to Cookham from London, and with Hilda away a good deal visiting her brother George who was ill, Spencer had renewed an acquaintance with a younger artist, Patricia Preece. Seeing her as fashionable, elegant and exotic, he began to spend increasing sums on gifts such as jewellery, clothes and perfumes. Patricia was herself involved with someone else, having lived with a school friend, Dorothy Hepworth, for many years. Both Dorothy and Hilda clearly found the developments worrying, and cracks appeared in both relationships. By 1935, Hilda had left Spencer, whilst he had become seriously indebted. He seems to have envisaged some sort of menage arrangement between all four of them, but as one might imagine, this was never really going to appeal to any of the women involved. In 1936 Hilda began divorce proceedings against Spencer.

In May 1937, the divorce was finalised, and Spencer immediately began to arrange for his marriage to Patricia Preece. However, once the service was over, Patricia and Dorothy headed off to St.Ives in Cornwall. Spencer followed a few days later but there was little harmony and he returned to London, the marriage unconsummated and his relationship with Patricia apparently gone. How different this must have felt to the joyous, mystical union he and Hilda had enjoyed back in 1925.

Realising that the wedding to Patricia was a sham and a disastrous betrayal of Hilda, Spencer sought to persuade Hilda to return with him to Suffolk, to the place where that first marriage had begun. His appeal failed and he travelled alone, again staying with Mrs Lambert in the same lodgings where he had spent his honeymoon in 1925. Catching the bus each day to Southwold, he produced one of his most popular and frequently reproduced paintings, Southwold (Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museum). The apparent easy jollity of the scene, with the striped deckchairs, the families sheltered from the breeze and the sunlight shining off the waves at the water's edge, serves only to remind one that our viewpoint, an observer on all that is happening below, is one of separation and thus knowing what had been happening to Spencer during this time makes recognition of this distance all the more poignant.

Both Hilda and Spencer had always been energetic and prolific letter writers, filling pages with long, wandering monologues pondering all manner of things. However, locked out of the new relationship with Patricia and estranged from Hilda, whose mental state, like Spencer's own, was quite fragile in the wake of events, letters became an important conduit for his thoughts. He continually petitioned Hilda for a reunion, and she finally relented but with the cruel irony of fate, Patricia's prevarications coincided with the diagnosis of Hilda's breast cancer, and she died in November 1950, Spencer's much longed for reunion still only a dream.

Yet, although Hilda was gone, Spencer continued to correspond with his wife, explaining what he was working on, what was happening in his life, and musing on their past together. Without a co-respondent to act as a corrective, the memories of these letters are shaped entirely according to Spencer's own fancy, but within them we can see the depth of feeling and love that he and Hilda had shared, and which he knew he had destroyed. Again and again we come across references to their visits to Suffolk, and with his incredible recall for detail we find ourselves taken for walks around the village and into the fields and woods, his affection for the place and its associations clearly second only to his beloved home town of Cookham.

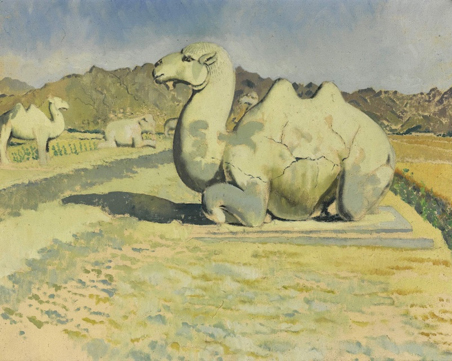

In a curious footnote to this story, there is a letter written by Spencer to Hilda in 1954, almost exactly four years after her death and just after his return from a visit to China. This journey was an oddity in itself, as Sino-Western relations were hardly at a high during this period of the Cold War. Responding to an invitation from the Chinese leader Zhou Enlai, a rather curious delegation of British visitors, including the philosopher A.J.Ayer, the architect Sir Hugh Casson, the writer Rex Warner and Spencer went on a long trip that included all manner of events and meetings, especially at cultural and artistic locations. One of these was a visit to the Ming Tombs, the fifteenth and sixteenth century mausoleums of the Ming dynasty. Returning home, Spencer picked up his pen and wrote about this strange place, at the time neglected yet still filled with large sculptural animals in a dusty dry landscape, as seen in his painting Ming Tombs, Peking (Private Collection).

Spencer wrote that he wished that Hilda had been there to see this place with him, as it so much reminded him of Wangford and their honeymoon. One might be at a loss to see how this comparison might come about but fortunately his letter expands his theme. After the guests had left their wedding breakfast back in 1925, Hilda and Stanley had gone for a walk through the lanes, pausing at a gate to look over 'a great plain' which they had imagined to be the future landscape of their life together. Each form of the landscape was seen as the events to come to them, though little did they know what for those events were to take. For us to speculate as to the similarities between the landscapes of China and Wangford is, to say the least, somewhat adventurous but perhaps the wide skies and unkempt bushes of Tree and Chicken Coops, Wangford (Tate Britain, London), painted in 1925, do indeed carry something which, almost thirty years later, took Stanley Spencer back to revisit the memories of his younger self, a self filled with hope for a loving future.