Anyone who has spent any time at all looking at Stanley Spencer’s work will recognise the descent into a rabbit hole that takes you straight to the very curious thought world he inhabited. So many strands from his life interweave; from his earliest childhood to his yesterday, tiny moments in his life are recalled with incredible clarity and then reinterpreted in pencil and paint to express Stanley’s feelings about them.

Drawings were a key part in this process. Sometimes large and elaborate, sometimes small and sketchy, drawings were central to the way in which Stanley’s ideas were developed and shaped into a coherent narrative.

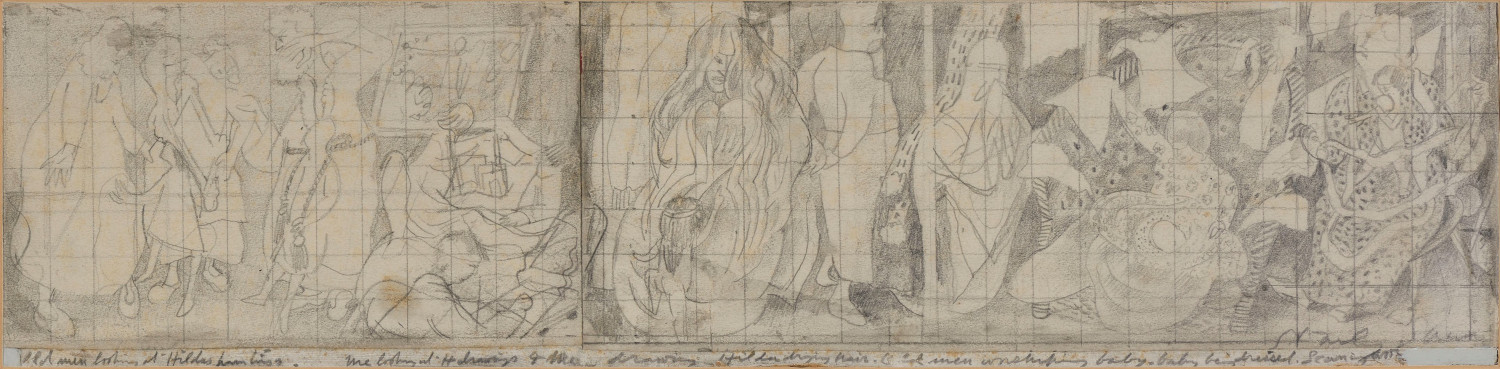

This rather compact drawing is a wonderful example of how this process unfolded. Using several sheets of paper joined together so that the action can flow from one image directly into the next, the overall impression is somewhat akin to a filmmaker’s storyboard.

Stanley Spencer - An Autobiographical Drawing, c.1943

There appear to be a small group of comparable drawings made around 1943 which use this panoramic format to tell a succession of stories. Stanley had used this method of developing the different elements of a composition from the 1930s onwards and in these drawings, rather like the predella of a renaissance altarpiece, he seems to have found it a good way to bring together what one might call his ‘incident’ images. These are clearly a mixture of both observed and imaginary scenes and they capture Stanley’s remarkable ability to create a permanent observed reminder of a fleeting moment. They are often, as here, squared for transfer to paintings although this rarely happened – Stanley’s ambitions for his work were often far beyond what was practically possible. He did however also annotate the drawings which is a great help to those trying to make sense of some sometimes rather abstruse images!

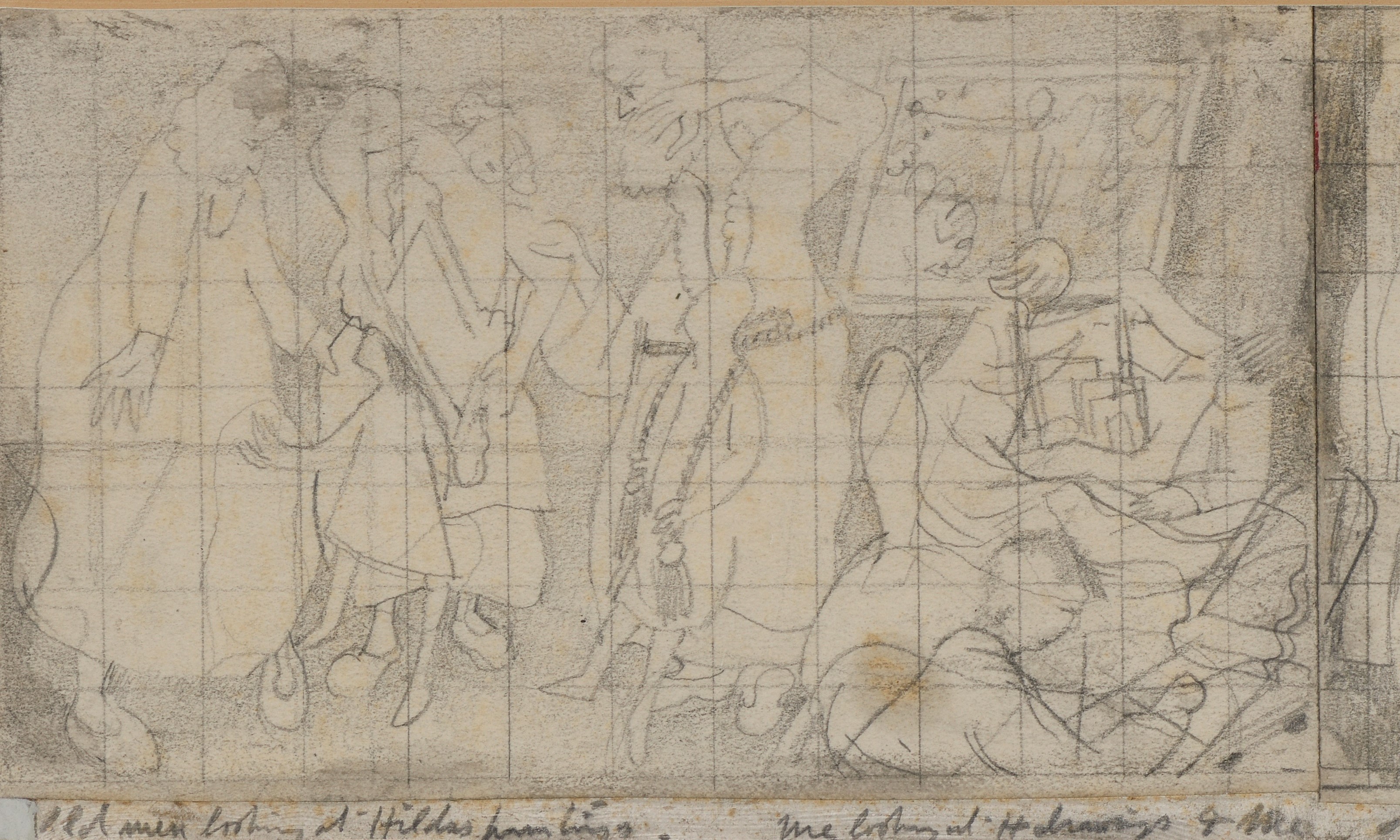

In this drawing the moments combine the mystical, such as the presence of the Old Men, a group of figures that he seems to cast in a rather angelic role despite their garb and attitudes and who pop up in a number of paintings around this time, and the everyday. Reading across the drawing from the left, we first encounter the Old Men when they are seen looking at Hilda’s painting. Although not explicitly stated, it appears that this is a painting by Hilda rather than of her and which would be supported by the overall context of the rest of the series of images (Stanley was also a great advocate of Hilda’s talent as an artist).

Hilda showing the Old Men her painting

We then find the Old Men later worshipping the baby, an action with obvious Christmas/Three Wise Men connotations. But between them are scenes of a more domestic nature, with Hilda drying her hair while Stanley draws her or Hilda dressing the baby. His unerring eye for detail in these vignettes is formidable and each scene is filled with tiny motifs that immediately bring it to life, such as the child’s clothes spread around the back of the chair as Hilda dresses the baby. Stanley’s distortions of each subject also play along with this approach, emphasising or diminishing an element to help the narrative of the whole. So therefore, not only is Hilda surrounded by the other clothes on the chair, the chair itself has grown, enveloping Hilda in a rather comforting embrace and allowing even more clothes to be shown, heightening the sense of domesticity and the arcane mysteries of the nursery. This device brings to mind another Spencer painting, the magnificent and touching Love Letters, now in the Thyssen Collection, where he enlarges the armchair in which Stanley and Hilda sit surrounded by their letters to each other, the act of reading seeming now insufficient to their simply absorbing the togetherness he evokes.

Hilda dressing the baby while the Old Men look on

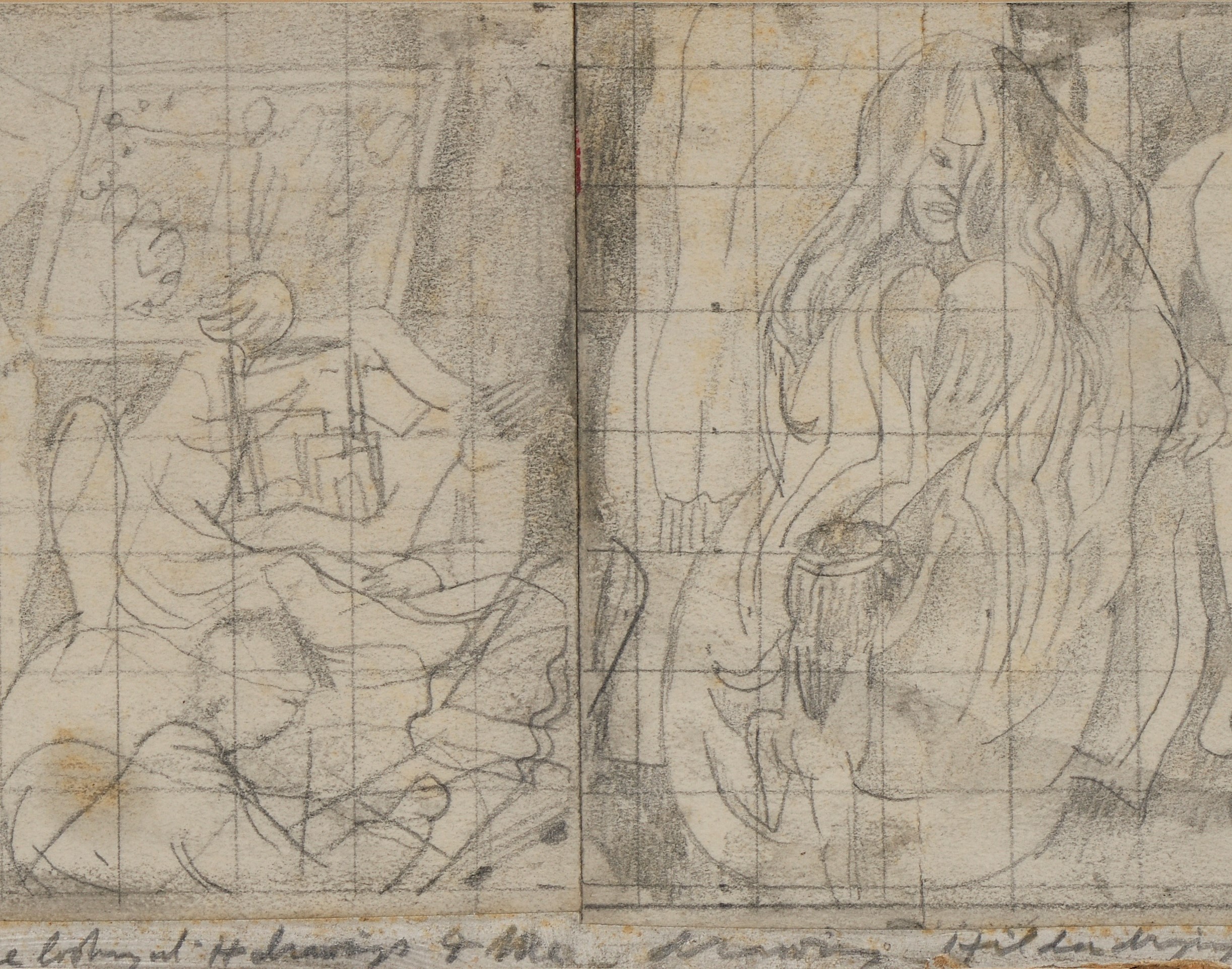

Another section of the drawing shows Stanley drawing Hilda while she dries her hair whilst behind another Stanley and Hilda look through a batch of Hilda’s drawings and as with the first part where the Old Men look at her painting, it is clear restatement of the extent to which the idealisation of Hilda is a key factor in so much of his work. This rolling frieze of images that together show Hilda in the various roles Stanley assigned to her - artist/muse/lover/mother – are, of course, idealised. This drawing was made almost a decade after he had left Hilda for his ill-fated second marriage and thus can be seen in the context of the almost constant need for Stanley to recapture and immortalise the ‘idea’ of Hilda and his prelapsarian idyll even long after her death.

Stanley drawing Hilda while another Stanley and Hilda look at Hilda's drawings

What I find so interesting about this drawing is that Spencer is giving Hilda the full treatment here, presenting her in succession as artist, muse and model, and wife and mother, a combination of features that to Stanley represented the ideal woman and which I don’t think I have seen so explicitly stated by him in another drawing of this type.

Whilst the drawing is ostensibly centred around the idea and ideal of Hilda, it is still hard to escape from those little pointers Stanley pops in to remind us that he is important here too! In the left section of the drawing we see a painting angled as though it on an easel. It seems to belong to the section which shows the Old Men looking at Hilda’s work. Although incredibly sketchy it shows a composition that relates very closely to Stanley’s early masterpiece The Apple Gatherers, now in the collection at Tate Britain. A painting that seems to evoke a strong sense of the vital connection between the central male and female figures, it would thus appear to be more than a random choice in the wider context of this drawing. However, I suspect that one additional factor in its inclusion could be to make sure that even though we are ostensibly worshiping at the altar of Hilda, we don’t forget Stanley’s own achievements!

Stanley Spencer - The Apple Gatherers (Tate Collection)

For Stanley, Hilda came to represent an ideal. Their relationship had failed by the mid-1930s and Stanley had sought to replace and augment it with his second marriage to Patricia Preece, an enterprise that failed utterly. However, by the time these drawings were made Hilda had been institutionalised after a breakdown and thus Spencer was doing what he did best, creating an idealised and stylised version of reality to express his own ideas and feelings about the subject.