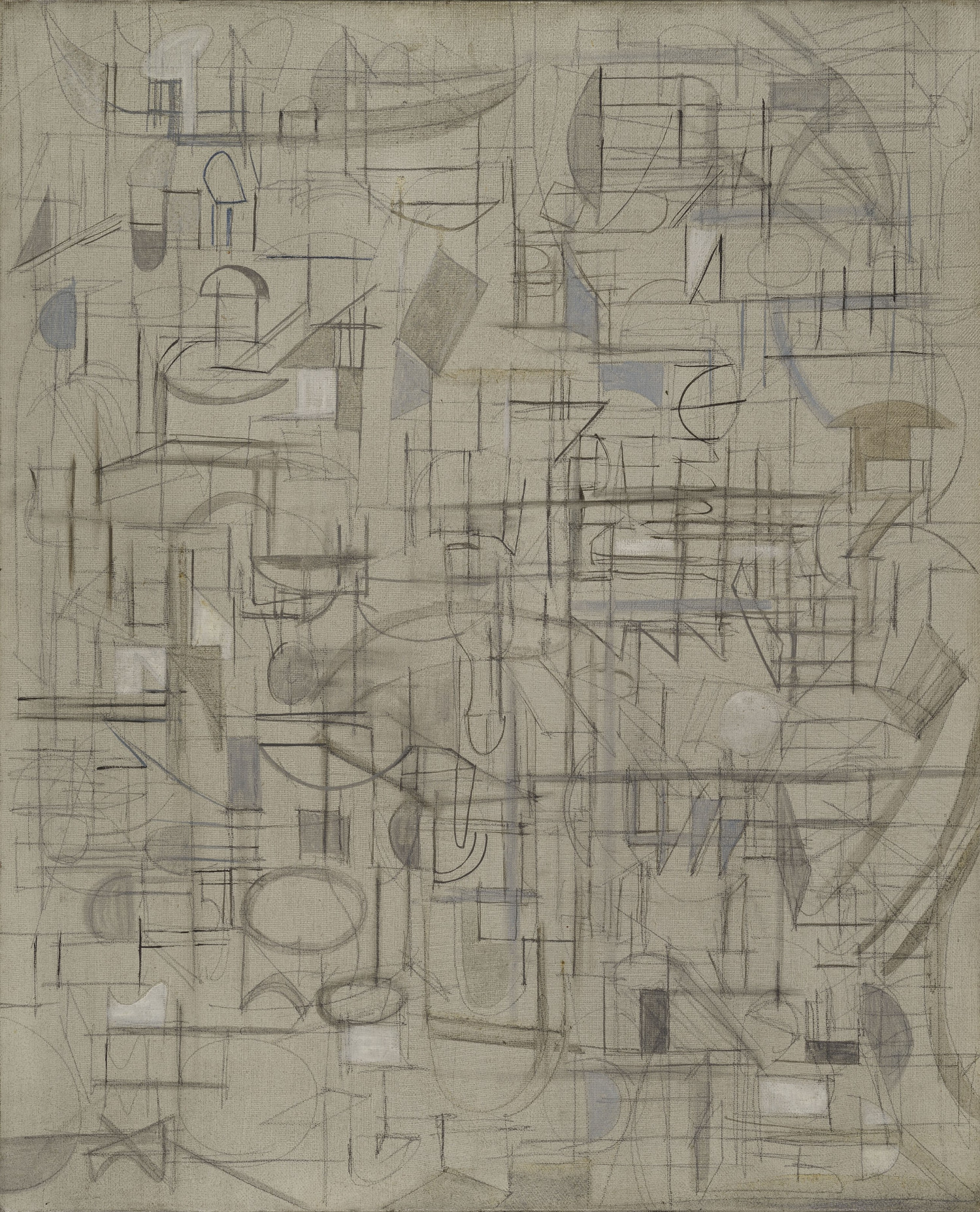

Sonja Sekula (1918-1963)

Now

oil, graphite and ink on canvas

61 x 50 cm (24 x 19 3/4")

Painted circa 1948-9

In 1971 the art critic Nancy Foote wrote an article for Art in America entitled ‘Who was Sonja Sekula?’ in response to a small exhibition of Sekula’s work held at Finch College in Manhattan. Sekula had died in 1963 at the age of 45 and in less than a decade since her death she had become a largely forgotten figure. In the years since that 1971 show, a number of exhibitions and publications have begun to reintroduce her distinctive but small body of work to the wider world and we can now see that she was an artist whose work deserves this wider recognition.

The basic facts of her life are quite well documented. Born in Lucerne, Switzerland on 8th April 1918 to a Hungarian father and a Swiss mother, her early years were relatively privileged. By 1934 she had set her mind to a career as an artist and studied in Budapest and Florence. In 1936 the family moved to New York and the following year she took private painting lessons from Georg Grosz, then an émigré in the USA. She enrolled at Sarah Lawrence College to study art and literature and by the early 1940s was mixing with some of the leading surrealists who had decamped to America during WWII. The decade from 1941 to 1951 was perhaps her most stable and successful and during this period she enjoyed her greatest successes. However, the mental instability that had dogged her since youth became more pronounced and the harsh treatment of the time for such illness filled much of the next few years. In 1963, a couple of weeks after her 45th birthday, she hanged herself in her Zurich studio.

The American art world of the post-war period has become deeply mythologised. It appears now as a cauldron of exciting and bold new approaches and ideas about art that produced the mega-stars who still define much of our attitude to ‘modern’ painting; Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, Jasper Johns, Willem de Kooning and others. For years the orthodox history of this period has focussed on the bold, bad, new and overwhelmingly male aura around the Abstract Expressionist artists, but as with most stories, there is another side. The complex connections and influences in New York in the early 1940s were many; the melding of the earlier influences of Cubism and abstraction with the in-person influx of major European figures such as Andre Breton, Arshile Gorky, Max Ernst and Piet Mondrian gave American art in that decade a perfect storm of energy and ideas that was quite unlike anything being produced elsewhere else.

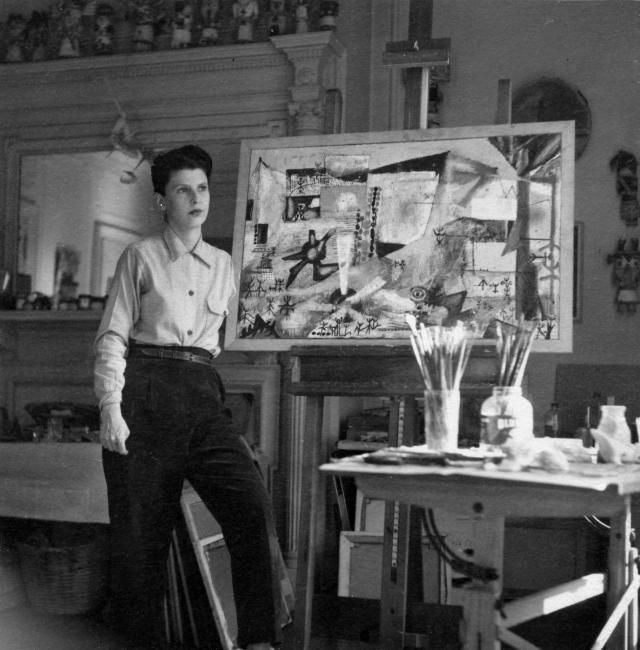

Sonja Sekula in Andre Breton's New York apartment, 1945 with her painting Untitled (1942)

So where does Sekula fit in to this? She seems to have fitted in very nicely. Through her studies at The Art Students League she met and became friends with Motherwell; by 1942 she was close to a number of influential surrealists, particularly Breton and Ernst, as well as knowing others such as Marcel Duchamp and Yves Tanguey and in 1943 her work was included in 31 Women Artists, a show at Peggy Guggenheim’s avant-garde gallery, Art of This Century. In May of that same year she was one of those included in the gallery’s Spring Salon for Young Artists alongside Pollock, Motherwell and William Baziotes. By 1945 she was lodging with Breton and the following year had a solo show at Art of This Century. In 1947 she moved into a studio at 346 Monroe Street where John Cage and Merce Cunningham lived and quickly became great friends with them. Cunningham rarely had his costumes designed by others, but in 1947 he asked Sekula to create his own one for Dromenon, performed that year.

In 1948, Sekula held the first of a number of solo exhibitions at Betty Parsons Gallery, the gallery perhaps most closely associated with leading Abstract Expressionist figures. Critics wrote positively about her work and sales were made.

Sonja Sekula in 1945

Now is a painting from just that point in her career and one that has long been out of the public gaze. In fact, it is entirely possible that it has been unseen since the early 1950s.

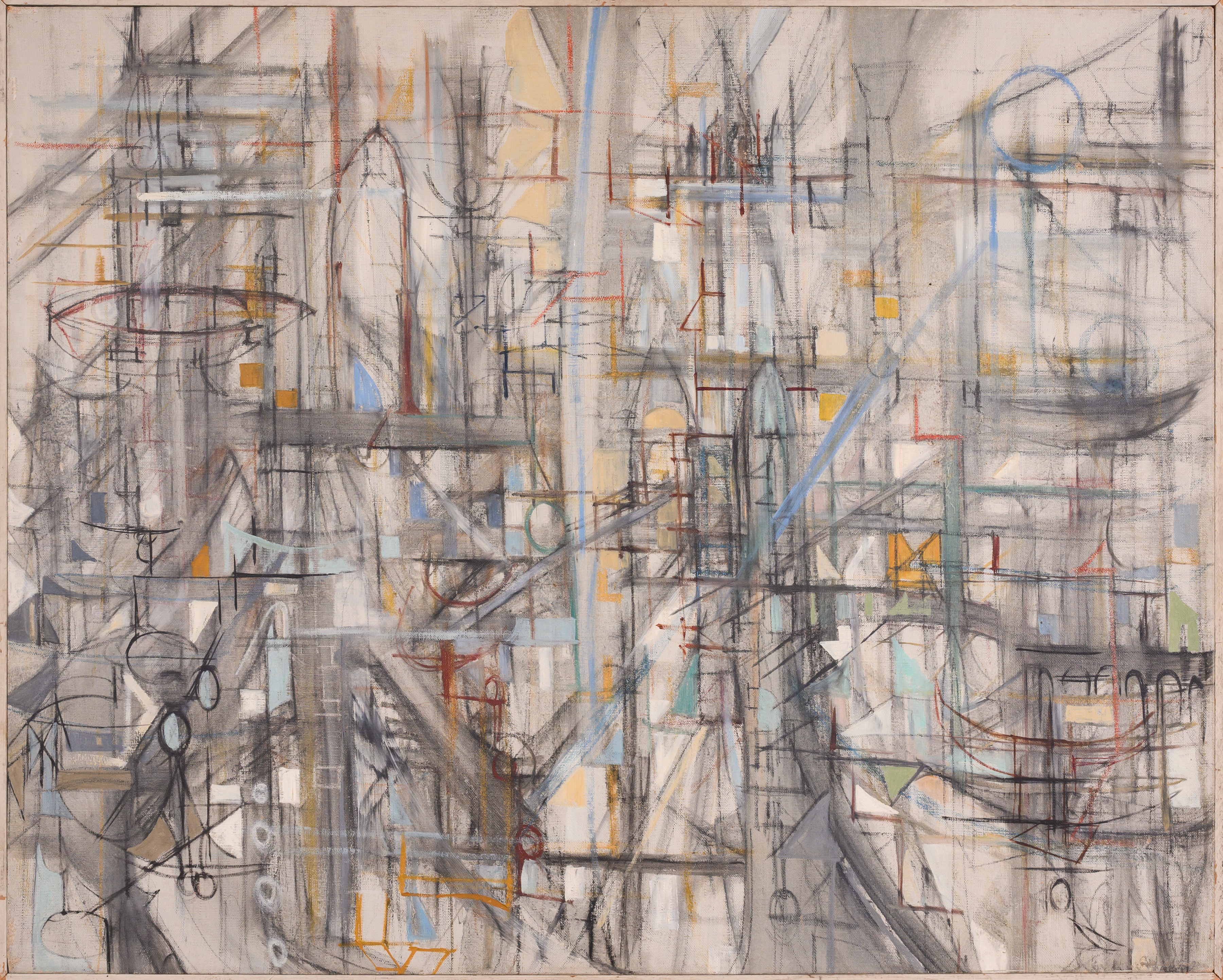

Like much of her painting from the 1948-50 period, Now exhibits a very distinctive approach to its making. Painted over a thin grey washed ground, the image is slowly built up with a network of tense lines, some in paint, some in ink and some in pencil. Areas of colour, pale blues, greys and whites, are used to highlight certain points. The eye is never allowed to rest but as we look across the image, shapes reminiscent of architecture and other forms begin to appear. They are never more than ghosts though, the hint of an arch or doorway, the shadows fallen on some steps, the prow of a barge. In this we can see that Now follows the path Sekula has taken in other paintings of the period, most notably her Williamsburg Bridge and especially 7 am (both in private collections) where the hints of forms build an ethereal image that remains tantalisingly just out of reach.

Sonja Sekula, 7 am, circa 1948-9 (Private Collection)

It is interesting to note that this fragmented approach to architectural motif appears in the studies that Philip Guston was making around this time during his travels in Europe and whilst we do not know if he and Sekula knew each other, several people in their circles do coincide, particularly John Cage who was close to both.

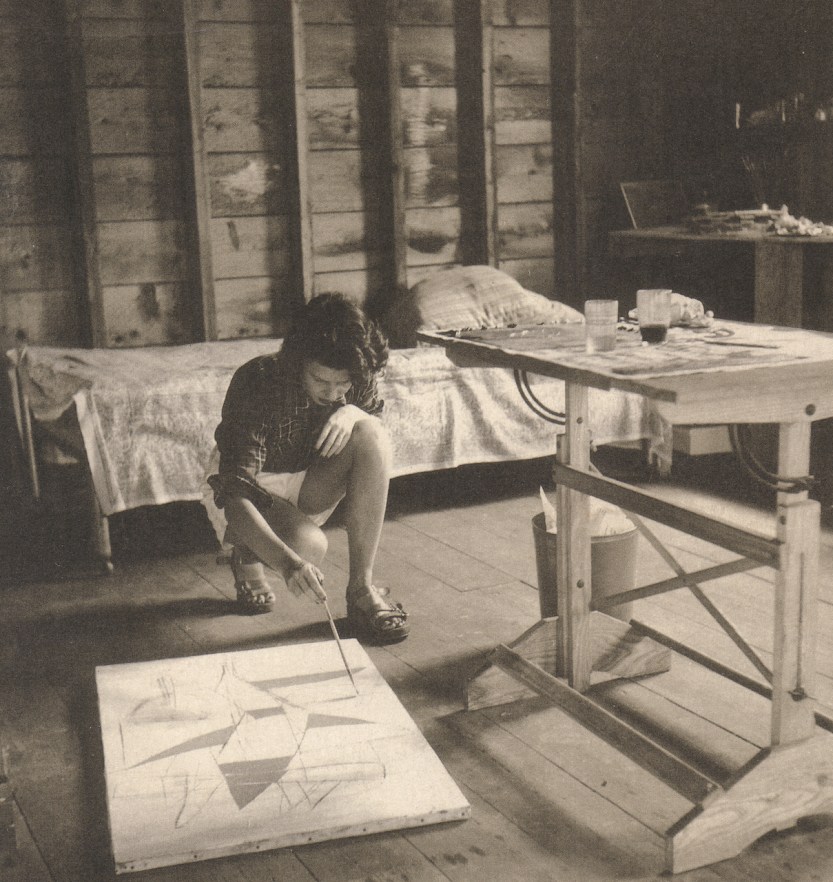

A photograph of Sekula from around 1946 shows her working on a canvas placed flat on the floor. In such a position it would be easy to work ‘in the round’ and study of the painting technique used in Now does suggest that it could well have been worked from different sides. The current orientation, in the absence of a signature on the front of the painting, follows that suggested by the title inscribed on the stretcher and the gallery labels.

Sonja Sekula painting at Long Island, circa 1946

Bearing labels for two exhibitions in London, it also helps us to clear up some inaccuracy that has been perpetuated in the biography of Sekula. In 1950 Sekula was included in a 3 artist show at The London Gallery, the innovative and interesting space on Brook Street run by the surrealist dealer and artist E.L.T.Mesens. The exhibition, which ran from 7-30 March 1950, was of work by Max Ernst, Sekula and a young sculptor, Sean Crampton. Little can be traced about the exhibition but to be shown in the company of Ernst suggests that Sekula’s work was well considered. It also bears a label for the Zwemmer Gallery, an important showing space for new art in London after the war.

Part of the famous London art book selling and publishing business of Zwemmer’s, the gallery gave exhibitions to many significant British and European artists during this period. The records of the gallery for this period are seemingly not complete and thus I have been unable to track down exactly the exhibition in which Now was included but it seems from other references to have been in or around 1950. The painting appears to have been acquired by the gallery and remained in their collection, forgotten in the store until it was sold in 2001. Acquired by a private collector, it has remained unpublished until now.

One might assume that by the time Now was made, the trajectory of her career was such that we would now surely know her and her work rather better than we do. But no. After her 1951 exhibition at Betty Parsons Gallery, she had a significant breakdown and spent a good deal of the 1950s in and out of institutions, initially in the US but then in Switzerland. She continued to paint, draw and write when she could, but the force of the art she made in the late 1950s onwards seems less consistent and perhaps less focussed. Even then it was recognised that the dealers wanted work that followed a signature style to allow them to market it and Sekula’s varied art, output and techniques did not allow for this.

Her personal life was, considering the conservatism of 1940s and 1950s America and the rather aggressively heterosexual ambience of the Abstract Expressionist cliques, also perhaps at odds with the mainstream. Since her late teens she had been involved in a number of relationships with women, including a particularly intense affair with the French painter Alice Rahon (through whom Sekula came to know Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera) and whilst she seems to not have been overtly out, there equally does not appear to be a great deal of subterfuge.

So, when we think about the question raised at the beginning of this article, are we now much further on in providing an answer? Since then, several exhibitions have allowed us to see the work and to begin to establish how it fits into the narrative of her life and the art of the time. The first major showing was in 1996 at Kunstmuseum Winterthur, Switzerland, travelling to the Swiss Institute in New York. This was followed by further exhibitions in Switzerland, at Kunsthaus Arrau in 2008 and in 2016 at Kunstmuseum Luzern. The latter held the exhibition, Sonja Sekula and Friends, an important opportunity to see her work alongside her contemporaries, the artists she knew and exhibited with, such as Pollock, Ernst, Roberto Matta and Wilfredo Lam. The most recent step on the path was in 2019 at the Katonah Museum of Art, New York where she was included in Sparkling Amazons: Abstract Expressionist Women of the 9th St Show. This exhibition looked at the women artists, including Sekula, who featured in the now historic exhibition 1951 9th St Art Exhibition, an event that is considered by many as a watershed moment for the Abstract Expressionist movement.

Does all this therefore make Sekula a ‘lost’ Ab Ex master? Is she, like many of the women artists of that generation, only now beginning to receive the accolades she deserves? Perhaps.

Her work is very free, especially in the late 1940s, and it draws inspiration from a variety of sources, particularly the Native American imagery that underlies much at that time. It is work that evokes the city and the constructed world. It has the feel of jazz, of Bird and Diz, and the execution, sometimes painted on the floor and in the round, fits with the ways in which we know her contemporaries challenged the established norms of painting. But there is also a thoughtful and contemplative side here. Much of her work exhibits an almost calligraphic approach to mark-making as for instance one sees in the paintings of Mark Tobey, and the delicacy of her use of colour from the mid- 1940s onwards suggests comparisons with artists like Paul Klee, someone a long way from Abstract Expressionism.

The simple answer is that she is her own painter and as such the gradual and growing awareness of her work does suggest that there is something more worthwhile here than the biography of someone in the right place at the right time. Her paintings have a presence which is quite arresting and although she rarely worked on a large scale, her important 1951 painting, The Town of the Poor in the collection of MoMA, New York indicates that her work can and does sit well with other more familiar names.

Installation shot at MoMA New York, showing Town of the Poor, 1951 by Sonja Sekula alongside works by Wifredo Lam, Louise Bourgeois, Alexander Calder and Maria Martins